When COVID-19 hit last year, thousands of Canadians were left with their flights cancelled. Airlines claimed that those passengers were not eligible for refunds and persuaded them into accepting restrictive travel vouchers, using the fine print on the ticket – known as fare rules – to motivate their decision.

This post goes over different types of fares with their cancellation and no-show policies, explaining how they apply to reward bookings and revenue flights.

What Are Fare Rules?

Fare rules detail things like cancellation policies, change procedures, and stopover allowances of an airline ticket. Unlike the tariff, which is the same for all passengers and flights, fare rules are specific to a booking class.

A booking class, sometimes called a fare bucket, represents the cabin and the flexibility of a fare. Airlines denote these buckets with letters.

The industry standard encodings are “Y” for fully refundable economy, “W” for premium economy, “J” for business, and “F” for first. When it comes to partially refundable and inflexible fares, different carriers use different letters.

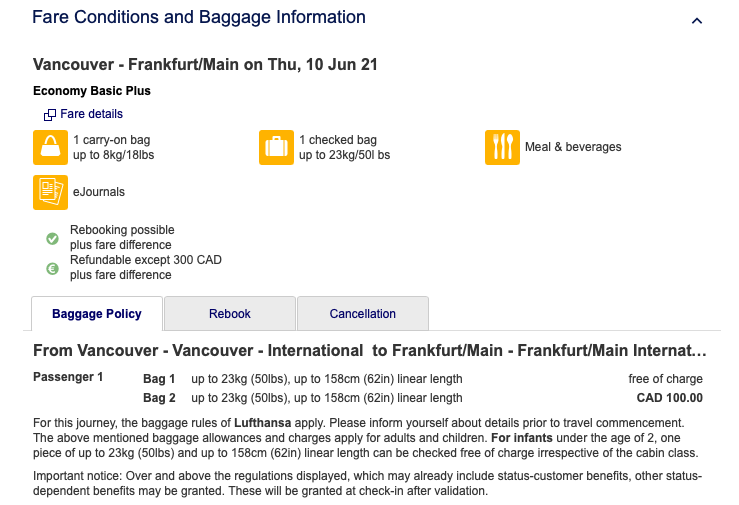

The airline website typically displays the fare details when booking a flight. The full text of the fare rules is bulky and dry, but it’s worth skimming through it to understand your rights as a passenger in case of voluntary changes or cancellations.

Carriers often make a more approachable version of the rules available, but they may not detail no-show policies, fee waivers, or the types of changes allowed.

Flight Cancellation Rules

Selling flexibility on a ticket can be a money-making machine for the airlines.

While a basic economy ticket and an unrestricted ticket can purchase the same physical seat on a plane, the price difference between the two can clock up to thousands of dollars. That’s the cost of being able to cancel a flight at any time, as opposed to forfeiting the ticket or accepting a travel voucher.

Generally, airline fares follow one of the following three cancellation policies.

Non-Refundable / Basic Fares

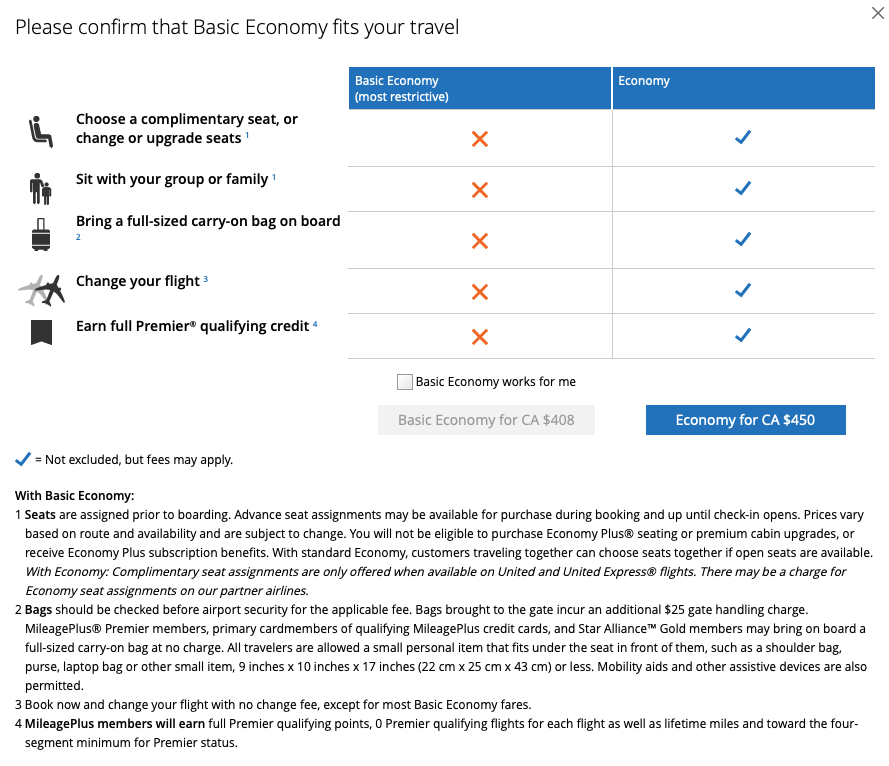

Non-refundable or basic fares usually have the lowest price, no complimentary baggage, don’t earn frequent flyer miles, and are not convertible to credit for future travel.

Both in North America and Europe, such basic economy tickets are often about $30–75 cheaper than other economy class options. Full-service airlines dissuade passengers from booking these fares, while low-cost carriers like Ryanair encourage people with prices as low as £20 roundtrip.

Should I not be able to make the flight, I lose hundreds of dollars. If I suddenly need to check in a bag, the airline may charge ancillary fees, which are higher than the savings of booking basic economy.

The one exception is a ticket that’s cheaper to forfeit than to rebook; Ryanair’s cheap flights throughout Europe are a common example.

As long as I don’t need the checked-in baggage allowance or the preferred seats, I’d rather try my chances with a £20 basic economy ticket and simply buy another one if I need a different flight, compared to paying £77 for the less restrictive fare category.

Semi-Flexible Fares

Semi-flexible fares typically allow using the value of the ticket towards future travel. In the case of international flights, the airline may issue a refund after withholding a penalty of a few hundred dollars.

In some cases, rules may be explicit about no refunds being given if the remaining ticket value is less than the cancellation fee. In a routing like, say, Boston–Tokyo–Moscow–Charlotte–Boston, if the value of the last segment is only $200 as opposed to a $300 penalty, the customer simply forfeits the $200.

Semi-flex fares are usually the lowest fare type available for premium cabins, such as business class or First Class.

Flexible Fares

Flexible, unrestricted, or full fares are cancellable at any time with no fee. Normally, they are two to four times more expensive than the next cheapest semi-flexible options.

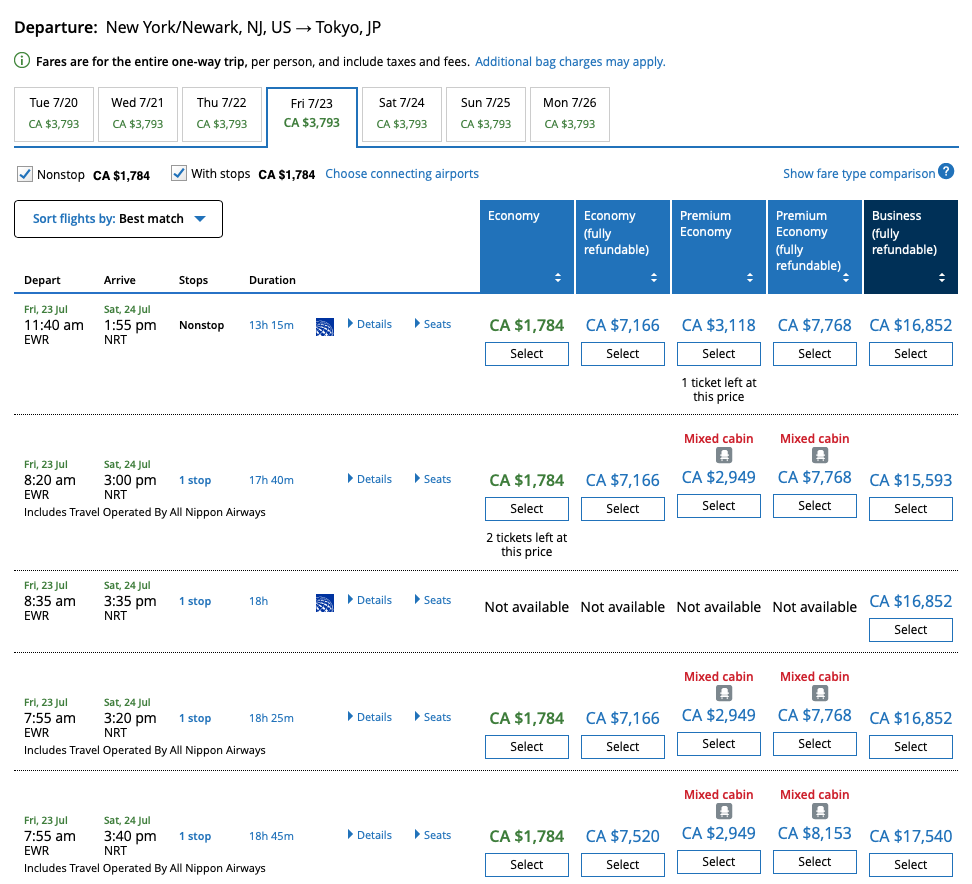

Let’s check out the rates for a United flight from Newark to Tokyo. The same economy seat retails for $1,784 on a non-refundable fare and for over $7,000 on a full one.

Combining Fares with Different Fare Rules

It’s not compulsory for the ticket to be cancelled as a whole – carriers typically allow the passenger to stop the journey at any point before the next upcoming segment. The cost is then prorated according to the price of each leg at the time of booking.

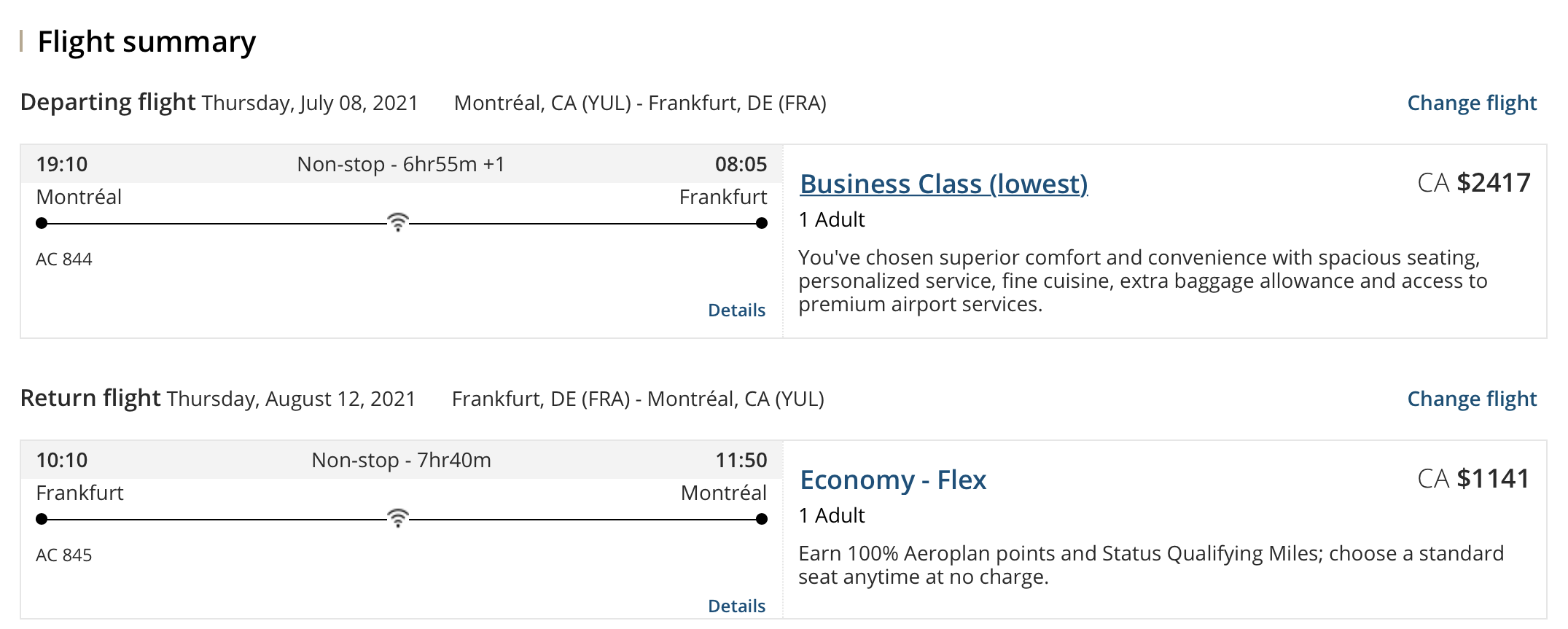

To better understand how cancellation policies apply, let’s consider an economy class roundtrip between Toronto (YYZ) and Bogotá (BOG) on Air Canada and United.

Let’s say the outbound flight is direct and costs $3,000 on a full fare. The return leg is semi-flexible, but only costs $1,000 and connects through Houston (IAH). It allows refunds at any time with a $300 penalty.

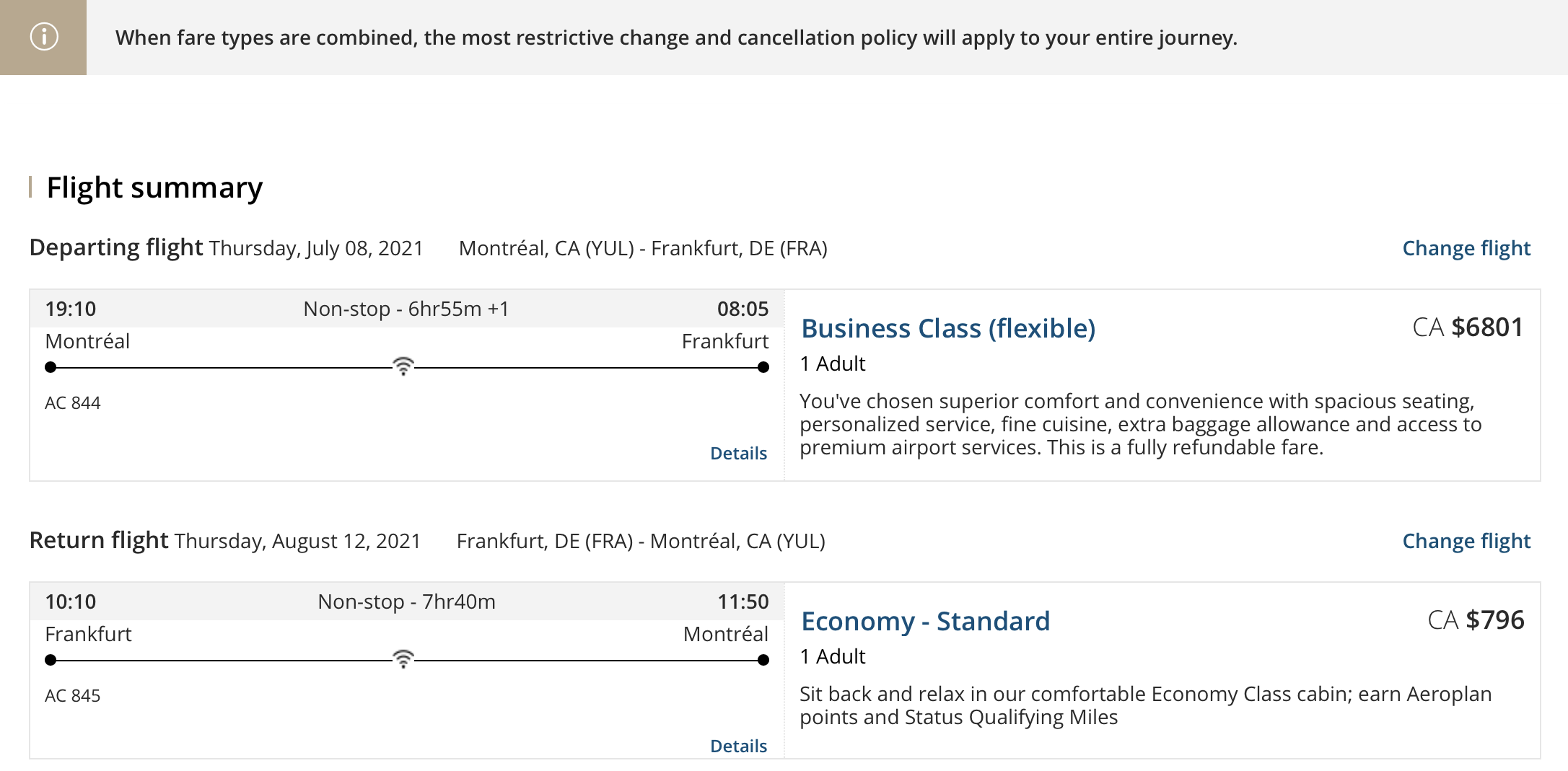

If the passenger were to cancel before departure from Toronto, they would receive $3,700 back. Even though the YYZ–BOG fare is flexible, the return leg is not. Airlines apply the most restrictive cancellation policy to the entire journey, regardless of the fare class of each segment. Air Canada warns customers about this during the booking process.

Had the passenger decided to remain in Bogotá and not take the return leg, they would have already burned through $3,000 worth of airfare. The first flight on the itinerary was less than 50% of the total mileage flown, but since refunds are prorated based on flight legs and not on distance, the amount that would go back to the customer’s card is just $700.

In case the trip were to end in Houston, which is the connecting airport for the return portion of the journey, the traveller would not have been entitled to any refund. The BOG–YYZ leg is treated as a single one-way bound, even though it consists of two segments. Contrarily, if IAH were a stopover point, the BOG–IAH and IAH–YYZ flights would have been priced separately and therefore considered independent.

As you can tell, combining fares with different cancellation rules is no different than setting money on fire, and you should only do it when there are no “compatible” seats on your flights of choice.

Notably, Air Canada’s Basic Economy is only combinable with itself. However, Air Canada doesn’t prevent passengers from booking a $7,000 unrestricted business class seat and an $800 “travel voucher” economy fare on a single ticket…

…when the same journey could have had a semi-flexible cancellation policy for half the cost.

No-Shows

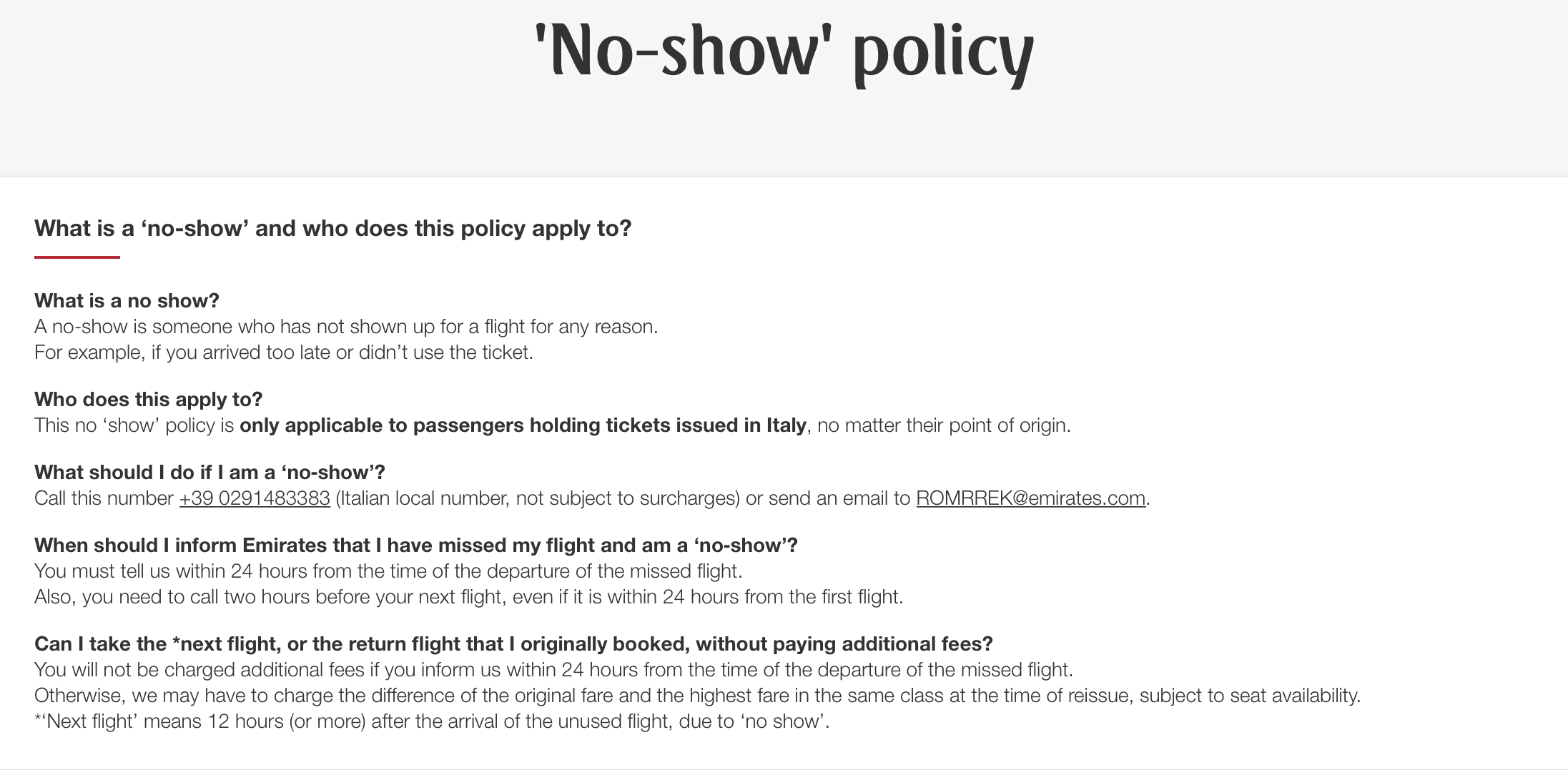

Refunds are processed according to cancellation rules only if the passenger gives prior notice to the airline. When a passenger does not check-in for a flight without giving prior notice to the airline, they are considered a no-show.

Depending on the carrier, two things can happen after – either the rest of the ticket is forfeited, or the passenger must pay a fee to reinstate their upcoming flights.

When an airline allows no-shows, fare rules will mention the fees and procedures. For example, if an Emirates passenger informs the airline within 24 hours that they missed their flight from Toronto to Dubai, they can pay an $800 fee and take the next plane for no extra charge.

However, if more than a day has passed, the customer has to pay the fare difference between his original fare and the highest fare in the same booking class. The highest fare usually means a full fare, so if the ticket was cheap to begin with, it might be optimal to forfeit it and buy a new one.

Airlines are accommodating with passengers who miss their flights because of a valid reason, such as being late to the airport or having a medical emergency. For people who purposefully book and skip part of their journey, carriers are less forgiving.

Airlines tend to sell one-way tickets to people with indeterminate and ever-changing travel plans, such as businesspeople, corporate travellers, or those who must depart on short notice because of personal emergencies. To reiterate the point about flexibility being the main moneymaker for the airlines, people who have precise travel requirements are generally willing to pay more.

What About Award Tickets?

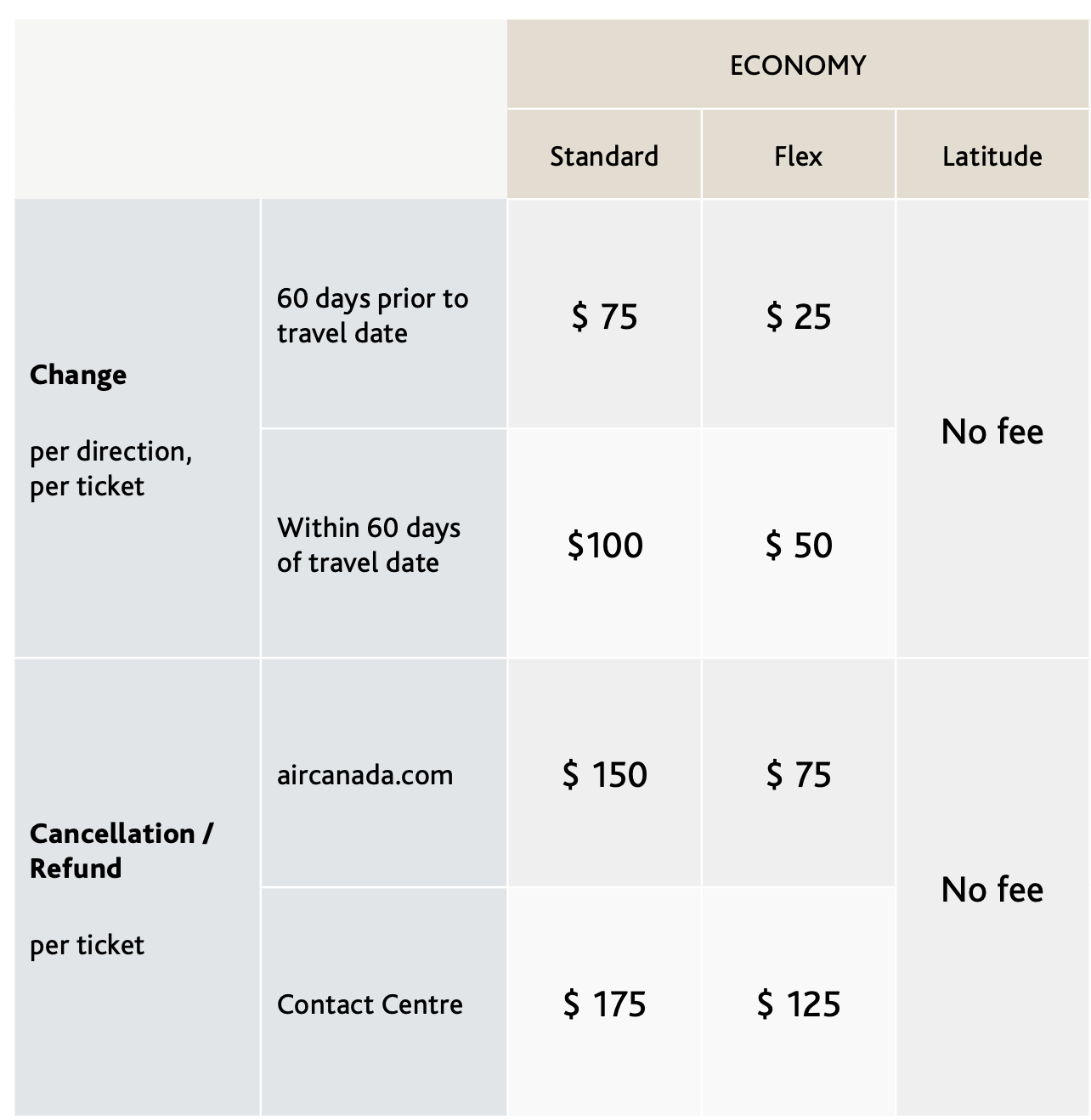

Flexibility is an often-overlooked benefit of award travel. Major airline loyalty programs available to Canadians, such as Aeroplan, British Airways Avios, and Cathay Pacific Asia Miles, allow voluntary cancellations for a symbolic penalty. The full schedule of fees and surcharges, stopover policies, and baggage allowance is available online.

Some carriers mimic revenue booking classes for award tickets. The new Aeroplan introduced Standard, Flex, and Latitude fares, but unlike their revenue counterparts, they are all refundable with a maximum fee of $175.

United, American, and Singapore KrisFlyer differentiate between “Saver” and “Advantage” awards, but the differences between them are availability and cost, not flexibility.

Conclusion

Cancellation and no-show policies are key components of airfare. By understanding them, passengers can find compatible fare combinations and leverage their rights when requesting refunds or dealing with accidental no-shows. Knowing when it’s cheaper to forfeit a ticket as opposed to paying for an unrestricted seat could save thousands of dollars.

Award tickets are exempt from the heavy premiums of revenue fare flexibility. Airlines are generally willing to redeposit the frequent flyer miles for a symbolic fee, which makes loyalty programs the way to go for speculative bookings, even when cash fares are competitive.