Welcome to the final installment of this trip report. After a profoundly gratifying three weeks spent in Russia and a gruelling 11 days on-and-off the Trans-Siberian Railway through to Mongolia, it was finally time to embark on the final 29-hour leg of the journey back to my hometown of Beijing.

We’d be continuing along the Trans-Mongolian Railway, the branch of track that follows an ancient tea-caravan route through the North Asian steppe and the Gobi Desert. We’d be travelling in the Second Class compartments, just like the previous train we took from Irkutsk to Ulaanbaatar, but this time we’d be on one of the trains operated by Ulaanbaatar Railway (UBTZ) rather than Russian Railways (RZD).

(There’s also a third option for travel along the Trans-Mongolian route: the weekly services from Beijing to Moscow operated by China Railway (CR). We didn’t get a chance to try the Chinese train this time around, but it’ll definitely be on the cards if I ever make a repeat journey.)

I didn’t find an easy way to book these trains online, so we purchased our tickets at Ulaanbaatar Railway Station a few days in advance. You’ll want to find the central ticket office building and head to the second floor for international trains. Payment is by cash only, and as of summer 2018, a one-way trip to Beijing in Second Class cost 300,000 Mongolian tugriks (US$120).

Ulaanbaatar Railway Station ticket office

Trans-Mongolian Railway | Ulaanbaatar Railway Train No.24

Cabin: Second class

Route: Ulaanbaatar to Beijing

Date: Thursday, July 19, 2018

Time: Departing 7:30am and arriving 2:35pm the next day

Duration: 29 hours 5 minutes

The Ulaanbaatar Railway service to Beijing departs at 7:30am, so we made the short 5-minute walk from the Best Western Gobi’s Kelso to the train station around daybreak. The hotel had provided us with a small to-go breakfast to begin the journey.

Ulaanbaatar Railway Station

The first thing you notice is the striking exteriors of the Mongolian trains to their Russian counterparts. In contrast to the dull grey exteriors chosen by Russian Railways, the Mongolian trains are painted in a bright lilywhite colour with streaks of pink splashed across the carriage bodies. The modern and stylish look of the trains almost felt a little out of place compared to the barren steppe and desert landscape in which they primarily operate.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) train exterior

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) train exterior

The eye-popping design continued into the interior of Carriage 3, in which we had been assigned Berths 31 and 32 in Compartment 8. I can’t say the colour scheme of green and pink was the most aesthetically pleasing, though.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Compartment 8

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Compartment 8

This was a Second Class train in which compartments are shared among four berths. However, as soon as the train began moving, Jessica and I shut the doors and rejoiced among ourselves because the two berths opposite ours turned out to be vacant and we basically had the entire compartment to ourselves.

Naturally, we decided to spread out across the two lower bunks, and we stowed away the upper bunks to open up the compartment and make it feel more spacious. Unlike the Russian trains, the bunks don’t fold up and down to transform between seats and beds; instead, the same surface acts as a seat by day and a bed by night.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Stowed upper bunks

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Lower bunk

Underneath each bunk was a large enclosed storage compartment, where we stored our luggage for the duration of the trip.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Storage compartment

At the end of the compartment is a relatively large table for eating and drinking. Each compartment is also given a thermos so that you don’t have to keep going back to the hot water boiler at the end of the carriage.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Table

Underneath the table was a 220V power outlet. Mongolia uses the European style of plug, so an adapter was needed.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Power port

Other features in the compartment included a storage rack with netting and hooks, a reading light at each berth, and a personal entertainment system with minimal programming.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Storage rack

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Reading light

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Personal entertainment

Jessica and I rolled the blackout shades down for a quick nap, saying goodbye to the scenery of the expansive Mongolian steppe outside. It’s fair to say that the outside scenery, when we woke up a few hours later and drew the blinds, caught us well off guard…

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Desert scenery

That’s right – we were now speeding through the vast Gobi Desert on our way to the China–Mongolia border. There was not a single soul in sight, but every now and then we’d pass by a small settlement or two. We’d zip by in a few seconds and then it’d be miles upon miles of empty desert once again.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Desert settlement

Jessica and I sat by the window, and for the first time along this entire train ride, we were truly transfixed by the scenery. There’s something about the endless stretches of sand that makes you wonder about the world in a way that the lush Siberian boreal forest simply does not. Who were the people who inhabited these tiny communities, surrounded by vast nothingness in every direction? What were their stories?

As we watched the Gobi Desert go by, we realized that deserts, as a landscape and even as a concept, was something that was still foreign to us as travellers. We simply haven’t spent much time at all exploring the deserts of the world up until now, and we both decided that we must fulfill that gap in our travels sometime soon.

Around this time, the train attendant came by to offer us a few light amenities, such as packaged tea, coffee, and some kind of Mongolian milk-based drink – I think it was airag. None of the train staff spoke much English, and I also tried to communicate with them in Mandarin to no avail as well. That’s the overzealous Chinese spirit within me, I suppose, assuming that everyone in our sphere should speak our language…

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Cup of airag

Anyway, we sipped on the airag for a while as we took in the scenery. Jessica couldn’t stomach much more than a few sips, whereas I tried my best to savour the taste but still didn’t like it very much in the end.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Absorbing the scenery

I decided to talk a walk through the carriage. The Mongolian trains are a pretty clear step up from the Russian trains; everything looks and feels just a touch more modern.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Train corridor

There are small ottomans that can be lowered into place along the side of the carriage.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Foldable ottomans

Further down, there’s a drinking water dispenser (hot and cold), which is where you come to fill up your thermos.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Water dispenser

The end of the carriage is where you’ll find the toilet and the train attendant’s quarters. The bathrooms are well-maintained and remained relatively clean throughout the journey.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Bathroom

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Bathroom

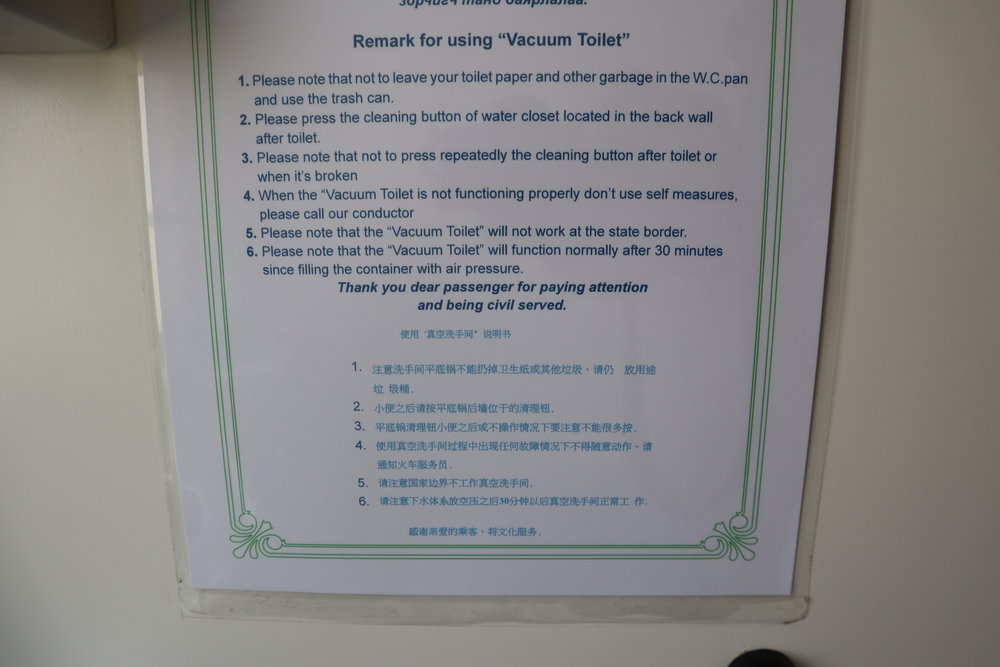

The store-bought hand soap was interesting, as was the detailed set of instructions on how to use the “Vacuum Toilet”.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Toilet instructions

The train even had a shower room available for use upon request, although regrettably I never got around to checking it out.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Shower room

Communities between Ulaanbaatar and Beijing are few and far between, and our first pit stop arrived about eight hours into the journey at Sainshand, a community of about 25,000 inhabitants. Stepping off the get some fresh air, I couldn’t help but marvel at just how striking the white train exterior looked in the desert sun.

Train at Sainshand

Train at Sainshand

There wasn’t much to occupy your attention on the platform besides the station building itself and a few vendors peddling their snacks and trinkets. Jessica and I walked along the length of the platform a few times in order to get some meaningful exercise.

Sainshand station building

Sainshand street scene

It would be another three hours until we arrived at the border, and during that time our snacks and instant noodles were in full flow. Time flew by in-between the usual routine of reading, chatting, and watching the desert landscape outside.

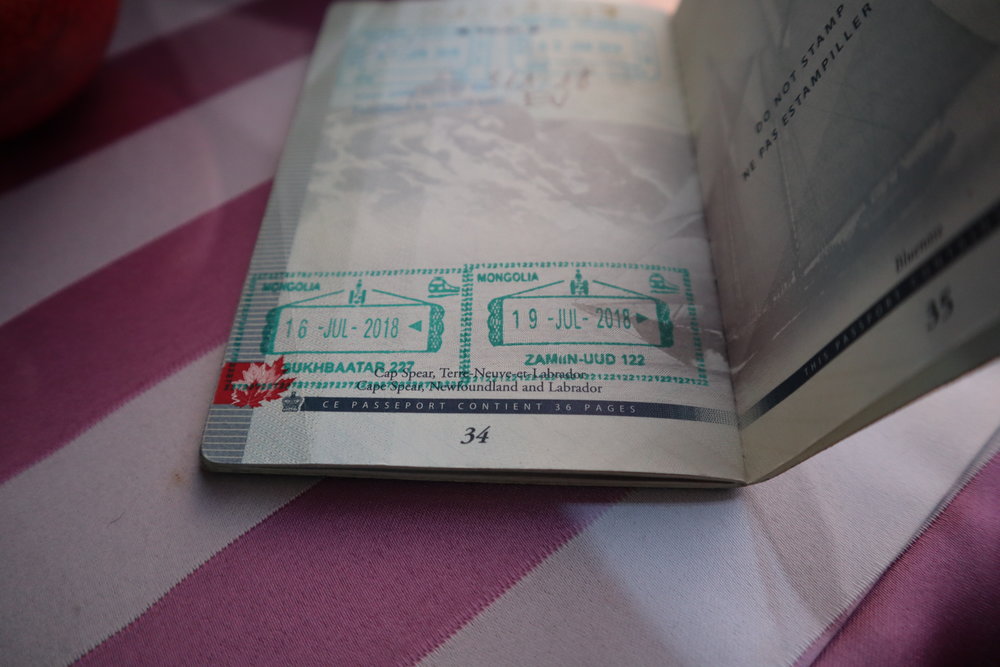

We weren’t allowed to get off the train at Zamyn-Üüd, the Mongolian border town. Instead, the border officials boarded the train and subjected us to the usual customs inspection before providing us with our exit stamps. And just like that, our brief sojourn in Mongolia had finished, the tiny train symbols on our passport stamps serving as a reminder of the journey we took.

Border official at Zamyn-Üüd

Mongolia exit stamp

The stop at Zamyn-Üüd took a good hour and a half, and by the time we traversed the China–Mongolia border, night had fallen. At this point in the journey, I was feeling quite burnt out and was itching to be back in Beijing and put my feet up for a few weeks. However, any sense of urgency I had in getting home proved to be futile, since our stop at the Chinese border town of Erlian (also known as Erenhot) was going to take an excruciating five hours.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Train schedule

You see, Mongolia and China have different track gauges, meaning that their railway tracks have different widths. It’s therefore necessary for any train passing through to undergo a bogie change, in which the bogies on each train car are removed and replaced with a set with differently spaced wheels.

As our train had its 1,520mm Russian-gauge bogies exchanged for a 1,435mm Chinese-gauge equivalents, all of its occupants needed to get off the train to go through immigration. It wasn’t immediately clear whether we needed to bring our luggage with us – everyone else seemed to take all their belongings with them as well, although Jessica and I left ours onboard and everything seemed to be fine as well.

We tried to clarify with the Chinese border officials stationed along the platform, but they didn’t seem to have an answer either. Nevertheless, it was tremendously satisfying to finally be able to speak the local language again.

In the immigration facility, we got to observe the crowd of people travelling along this route. It was a good mix of Chinese and Mongolian nationals making the journey across, together with adventurous foreign travellers such as ourselves.

Since we still had over four hours until our train would start up again, Jessica and I decided to go exploring the city of Erlian by night. (While Erenhot is the traditional Mongolian name for the city, Erlian is the short-form once you transcribe it into Chinese and take the first two characters.)

Erlian Railway Station

Erlian Railway Station

The city is home to about 75,000 people and is very much centred around its role as a railway border town. Many signs are written in both the Chinese and Mongolian script, and there’s a host of hotels and guesthouses littered within a few minutes from the train station.

Erlian steet scene

Jessica and I went for a bowl of late-night beef noodles at a small restaurant, which was nothing short of heavenly after three weeks of eating unfamiliar foods in Russia and Mongolia.

Besides being the biggest settlement on the Mongolia border, Erlian is also known as a place where many dinosaur fossils were discovered, and so dinosaur motifs are littered throughout the city. There’s even a mildly famous structure of two kissing dinosaurs spanning the road leading into Erlian, although we didn’t get to catch a glimpse of it this time.

Dinosaur-themed bench in Erlian

After our satisfying dinner, we walked a few more blocks, but there isn’t much going on at this time of night so we headed back to the train station. A group of Aussie and Dutch travellers had bought some beers from the convenience store opposite and were kicking it on the steps to the train station, so we joined them in order to pass the time.

Our train wasn’t scheduled to depart until 2am, by which point we were truly exhausted, and fell into a deep sleep pretty much right as the train began moving.

Departure board to Beijing

We awoke at about 10am, just as the outside scenery began to grow more and more familiar.

Trans-Mongolian Railway (UBTZ) Second Class – Scenery in China

At this point, there was only about four hours left to go in our audacious train journey from Moscow to Beijing, and I couldn’t help but look back on the past 12 days with a tinge of wistfulness. I knew I was checking off a major bucket list item, but I also felt as though I would really miss the day-to-day life onboard the train – the rumble, the scenery whizzing by, the simplicity of life – in the weeks and months to come.

I spent the remaining time finishing off a book and working offline on my laptop, before – and pardon me if this is too much information – heading to the bathroom for a No. 2 for the very first time on this entire train ride.

That’s right, I was able to “hold it in” for the 41-hour train to Novosibirsk, the 31-hour train to Irkutsk, the 22-hour train to Ulaanbaatar, and the first 27 hours of the final leg to Beijing, but I succumbed to my bodily functions and simply had to go at the 11th hour (or should I say, the 122nd hour). I suppose all those bowls of instant noodles were bound to eventually take their toll.

As our train pulled into the Beijing city limits, we packed up our belongings for the final time and got ready to disembark. The summer heat in Beijing was unbearable as we stepped onto the platform at Beijing Railway Station –sweltering doesn’t begin to describe it – and the realization quickly settled in that we’d be battling this blanket-like heat throughout the rest of the summer.

Arrival at Beijing Railway Station

Conclusion

The Mongolian train made for a delightful ride, and I’d recommend trying out at least one segment on these trains if you’re contemplating a trip along the Trans-Mongolian route. In particular, if you’re interested in taking a trip like this but don’t want to deal with the challenges of going all the way through Siberia, then a train ride simply between Beijing and Ulaanbaatar would certainly be a rewarding experience as well.

I gave my parents a big hug as they picked us up at the train station, and took a moment to digest the sheer magnitude of the journey we had just completed. 123 hours on the train, 7,261 kilometres, 12 days, three countries, five cities, and countless bowls of instant noodles later, the Trans-Siberian Railway was well and truly checked off the bucket list.

Even now, looking back, it still doesn’t feel real sometimes. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to take this trip, and I’d do it again in a heartbeat if the chance presented itself in the future.

Fantastic post, Ricky. I came across your site a few weeks ago and I’ve been enjoying reading through all your entertaining and informative posts. I’ve been playing the miles & points game for some time (50 countries and counting) but I’ve still learned some new tricks from your site.

Looking forward to reading about your experience of Asiana first class. Asiana was my second even first class flight and I have good memories.