The line between cash and points is constantly becoming more blurred. The more we talk about high-value redemptions, the more it becomes clear that loyalty rewards have serious value.

But how do we measure the value of our miles and points? After all, there are monetary costs and other limits to earning points. We can’t pursue every available credit card, as much as we’d like to. How should we decide which ones are worth it?

Today, I’d like to explore a few different ways to view the earning side of the equation, in what I hope will become the first in a series of posts on this complex topic. I’ll show you how I like to do it, and why you might be doing it wrong. Buckle up!

In This Post

- Definitions

- Net Gain

- Return on Spend

- Return on Fees

- Comparing Constraints: Which Metric is Better?

- Infinite Returns: Where Rates Don’t Matter

- Calculate Your Gains Now!

- Conclusion

Definitions

When deciding whether to apply for a new credit card, we always need to consider the costs and benefits of opening that account, versus not getting the card at all. Ideally, what we stand to gain is worth the effort compared to other credit card strategies.

To get started, let’s review some familiar variables in the miles and points equation:

- Spend is the dollar amount of the purchases put on the card. When measuring the value of welcome bonuses, this is the minimum spend requirement.

- Earn rate refers to the number of points awarded per dollar spent on everyday purchases. This can vary by merchant category.

- Points are an amount of rewards, denominated either in a loyalty program currency (miles or points) or as cashback. With respect to the earning equation, this can refer to a welcome bonus, rewards on everyday purchases, other offers such as an award for referring a friend, or any combination thereof.

- Value refers to what that loyalty program’s points are worth in Canadian dollars, also known as “cents per point.” For this exercise, I’ll be using Prince of Travel’s points valuations, but you can plug in any number based on your typical redemptions.

- Perks may include any quantifiable benefits, for example if you can assign a dollar value to lounge access. For simplicity, I’ll treat this as zero, but you can adjust it as you see fit.

- Fees include all costs involved with a particular credit card, such as annual fees or transaction costs.

- Rebates include any cash kickbacks to offset Canadian-dollar fees, where the bulk of the card’s value is awarded as a loyalty program currency.

In particular, it’s important not to confuse spend and fees. Spend is going through the card for other goods and services, while fees go to the card itself for the privilege of opening and maintaining the account.

In other words, spend is money you would have spent with or without the card, and fees are money you only spend because you have the card. The distinction is subtle but critical.

Net Gain

The easiest way to measure if you’re getting ahead is to ensure that you get out more than you put in.

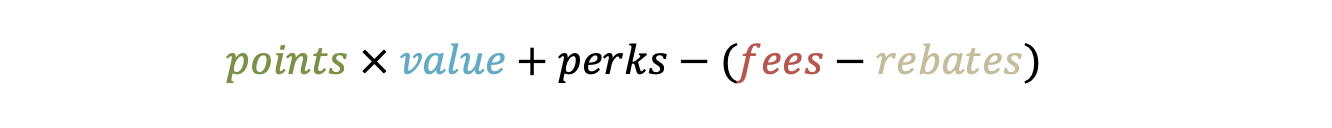

Points can be broken down further:

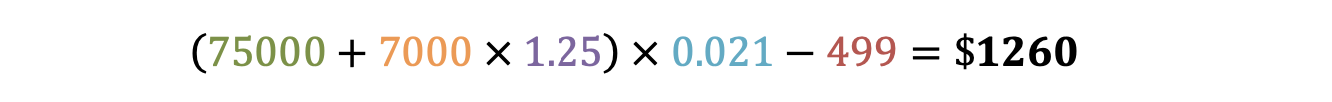

As long as the result is greater than zero, the card is a winner. Take the American Express Business Platinum Card, with the biggest welcome bonus in Canada, at 75,000 Membership Rewards points.

It should be no surprise that the card with the biggest bonus has the most value, despite a high annual fee. For hitting the minimum spend requirement, you’ll gain at least $1,260 in value in the first year.

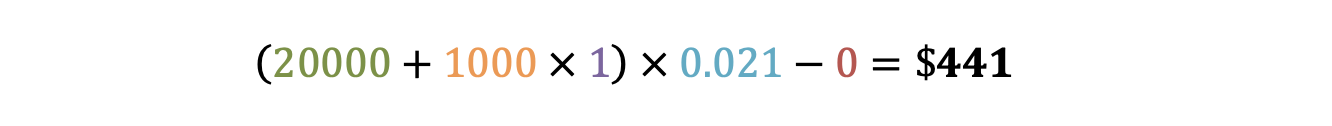

Compare this to a first-year-free card with a smaller bonus, like the TD Aeroplan Visa Infinite. With a gain of $441, it would take about three of these cards to equal your haul with one Amex Business Platinum.

While that’s a fine strategy if you prefer not to front annual fees out of pocket, it’s a much slower way to accumulate points. Pay-to-play offers with high annual fees can build up a usable rewards balance much more quickly, if the price is right.

Regardless, Net Gain is always relevant because there’s an opportunity cost to every credit inquiry. For each new card you open, there’s a temporary ding on your file that makes it harder to apply for the next card. So even if speed is your goal, size always matters.

If your spending power is high and you don’t mind paying annual fees, Net Gain should be your only concern, as you try to maximize the value of each credit inquiry.

Return on Spend

Although premium credit cards are the fastest way to earn points, the minimum spend requirements are often quite steep, and they aren’t achievable for everyone.

Return on Spend is a useful metric if your expenses are limited. In that case, it’s important to prioritize spending opportunities where your efforts will be the most efficient. Otherwise, your progress towards bigger gains will be slowed.

I’ve often seen Return on Spend described in terms of the everyday earn rate. But to get a full accounting of Return on Spend, we also have to incorporate bonuses and fees into our calculation.

For a no-frills card, Return on Spend is easy to calculate. Let’s take the entry-level TD Cash Back Visa Card, which has no fee, no welcome bonus, and awards 1% cashback on groceries, gas, and recurring payments. In the absence of a minimum spend requirement, let’s presume that you spend $1,000 on the card.

We don’t even need to use a formula – we can intuitively see that Return on Spend is simply equal to the category earn rate.

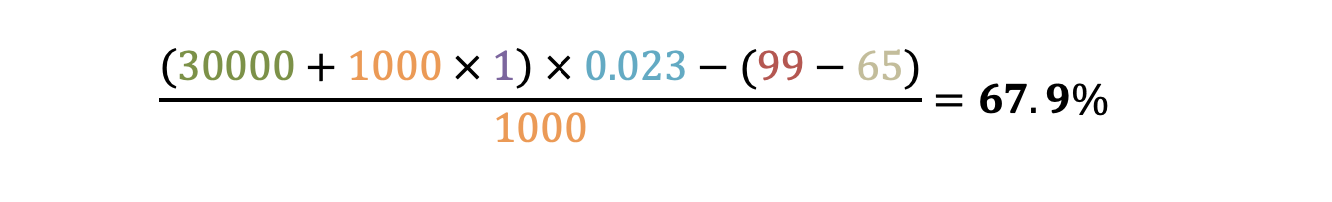

Now let’s add some bonuses and fees, with the MBNA Alaska Airlines World Elite Mastercard: 30,000 miles upon spending $1,000, with a $99 annual fee and a $65 rebate for applying through Great Canadian Rebates, and an earn rate of 1 mile per dollar.

By spending $1,000, you’ve gained $713 worth of Alaska Miles minus a net cost of $34, for a total Net Gain of $679, or 67.9% Return on Spend.

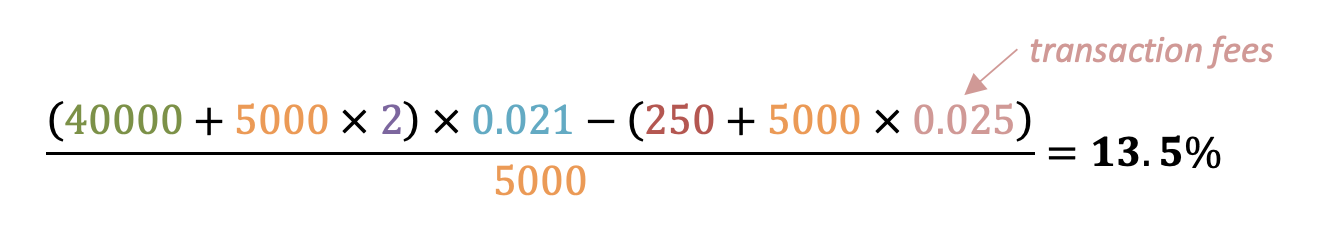

Let’s also look at the impact of transaction fees. Take the American Express Business Gold Rewards Card, used to pay $5,000 in taxes to the CRA via Plastiq at 2 points per dollar, with transaction fees at 2.5%.

Here, you’ve gained $1,050 worth of Membership Rewards minus a total cash cost of $375, for a Net Gain of $675 on $5,000 spend, or 13.5% Return on Spend.

Between these two examples, it’s much more efficient to pursue the MBNA Alaska card, because the minimum spend requirement is 5 times lower for the same Net Gain. For low spenders who’d just barely meet the spending threshold for the Amex Business Gold bonus, within that same 3-month window there’d be more value in tackling the MBNA Alaska bonus plus $4,000 in spending targets on other cards.

Clearly, Return on Spend is a good metric for lower spenders. Progress towards a worthwhile welcome bonus will always beat everyday spending, so it makes sense to focus your efforts on them.

However, if you spend so much that you run out of cards you can apply for, eventually you’ll inevitably have to put some ongoing spending on your cards. Any additional purchases beyond the minimum spend requirement will revert back to the base earn rate, just like how you’d measure your returns on a no-frills card.

At that point, Return on Spend drops dramatically. For example, let’s say your business has $10,000 per month in expenses.

In your first year with the American Express Business Platinum Card, you’d have a Return on Spend of 3.5%. In the second year, with an annual fee but no welcome bonus, it’d be 2.2%. These low numbers don’t really show the value you’re getting.

Return on Fees

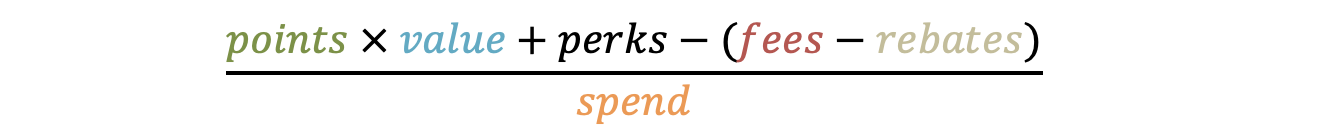

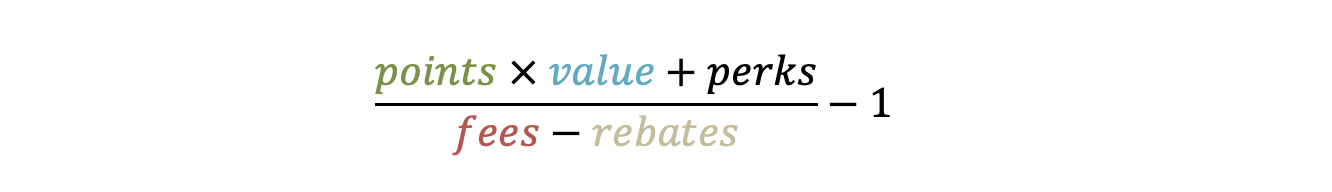

Another way to measure your rewards is by looking at the Return on Fees. Here’s the formula:

Notice that spend doesn’t appear anywhere in the equation. Rather than measuring how efficiently we’re turning our spending power into points, now we’re calculating how efficiently we turn our money into points.

This is a better metric for higher spenders, or if you have a one-off expense that spikes above your usual rate of spending. It’s also useful if you’re averse to paying high annual fees up front for value that you won’t realize until later.

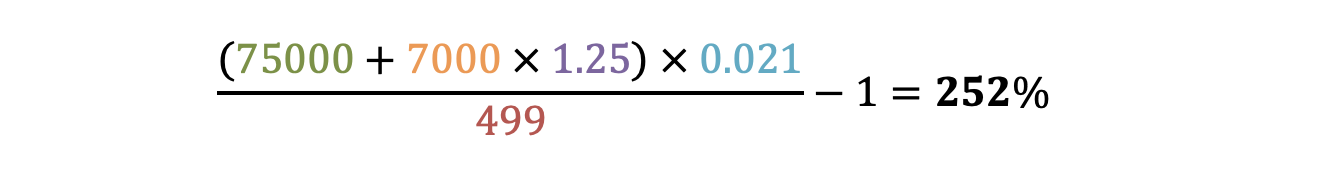

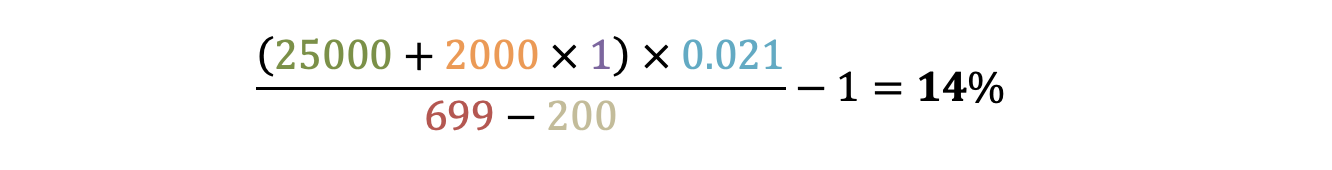

Let’s revisit the Amex Business Platinum, this time looking at a percentage gain instead of an absolute gain.

An upfront payment of $499 buys $1,759 worth of points. We’ve grown the value of our annual fee to 3.52 times its initial value, for a gain of 252%. This is undoubtedly an awesome rate for a guaranteed return, but how does it stack up against other credit card bonuses?

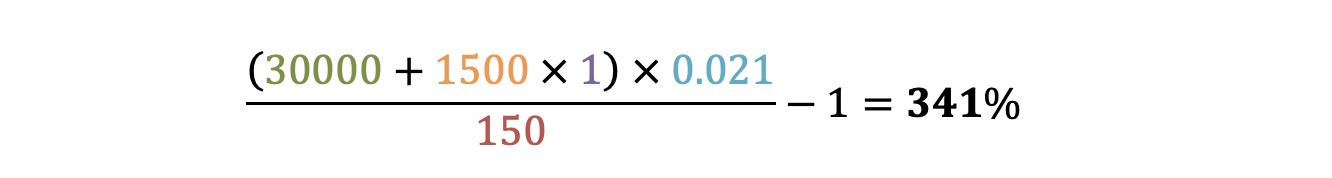

The American Express Gold Rewards Card offers $662 in gross value minus a $150 annual fee, for a gain of 341%. Despite a smaller total bonus, your upfront fees are actually more efficient because the amount you put in is quite a bit less.

We can also clearly see why we should avoid weak bonuses and weak redemptions. The American Express Platinum Card currently has a very poor offer.

While this offer is still worth more than its cost, it pales in comparison to other cards, let alone to its own historical highs last summer.

It’d be even worse if you were to redeem your points for a statement credit at 1 cent per point.

By applying for the card now and cashing out at 1 cent per point, you’ve turned your net $499 annual fee into $270 in rewards. Your costs have shrunk to 0.54 times their initial value, for a loss of 46%. (This also shows you why cashing out MR points at 1cpp is almost never a good idea.)

Furthermore, it’s also apparent why carrying a balance is so damaging. In the formula, interest payments would fit under fees, torpedoing your gains.

Any offer with a negative Return on Fees must be absolutely disqualified from consideration. You’d be better off not having the card at all, even if it means paying cash and earning no rewards!

Comparing Constraints: Which Metric is Better?

On a basic level, there are three primary constraints that will determine which metric is best for you:

- Use Return on Spend if you’re limited by your ability to spend

- Use Return on Fees if you’re limited by your ability or willingness to pay annual fees

- Use Net Gain if you’re limited by credit inquiries

However, even though my spending is indeed limited, I’ve moved away from using Return on Spend to measure the value of welcome bonuses. Instead, I believe that Net Gain and Return on Fees do a much better job of representing how I get ahead through my credit card pursuits.

Return on Fees is very similar to Net Gain, but represented as a rate instead.

I find this more useful, because it shows the number of points you get out, for the amount of money you put in. In other words, “points per cent” – it’s the inverse of the familiar “cents per point” concept!

By evaluating both sides in the same terms, we can see if we’re truly getting ahead on our travel goals, as opposed to paying cash outright. This helps guide the best ways to earn points, and the best ways to burn them.

Therefore, I prefer to view my gains relative to what I put in, not as an absolute increase. I like to look at annual fees as a way to effectively purchase X points for Y dollars, rather than simply X – Y worth of bonus value coming my way.

So how does spending fit into the big picture? Well, I no longer see Return on Spend as a meaningful measure of value. To me, it simply represents discounts on my spending, rather than growth of my annual fees.

Instead, I prefer to view minimum spend requirements as a black-or-white condition that is either met or not met. I only use minimum spend requirements to rule out unachievable bonuses. Of course, if there are transaction fees or inorganic efforts involved with meeting that requirement, those considerations come into play too.

And once I’ve maxed out my credit inquiries and hit all my welcome bonuses, it really does circle back to basics. At that point, everyday earn rates are the only consideration left – and only then do I use Return on Spend.

Infinite Returns: Where Rates Don’t Matter

Previously, I mentioned that Net Gain is a good metric if credit inquiries are your primary constraint. That would imply that you’re unconstrained by your spending power and by the money you can put towards annual fees.

Theoretically, this means you could have unlimited inputs. Does that mean it’s also possible to achieve unlimited outputs? Can we attain infinite rates of return?

Mathematically, in fact, yes: any time we divide by zero, our gains will be infinitely higher than our nonexistent costs.

You’ll see infinite Return on Spend on offers that have a first-purchase bonus, but no minimum spend requirement. These points can be acquired with no spending power cost.

If you’re normally limited by spend, these bonuses are a great way to increase your total earnings, without encroaching on your ability to pursue other offers that do have a spending requirement.

Meanwhile, you’ll see infinite Return on Fees on no-fee cards and first-year-free offers. These points can be acquired with no money cost.

If you’re normally limited by fees, these bonuses are a great way to increase your total earnings. This would be appealing if you can’t or don’t want to set aside an initial cash cost, in exchange for delayed gratification in the form of points and travel perks.

In both of these cases, your primary metric becomes useless because your primary constraint is no longer limiting you. Instead, you can fall back on using secondary constraints to rank no-spend or no-fee offers.

If you’re usually limited by spend, use Return on Fees to determine if no-spend offers are worthwhile. Or if you’re usually limited by fees, prioritize no-fee offers either by Return on Spend (if you can apply for new cards faster than you can spend) or by Net Gain (if you can spend faster than you can apply for new cards).

In fact, any of these offers are great for beginners. That way, you can start building your points balances before you’ve determined how you personally value each rewards currency, and before you have specific redemptions in mind. Indeed, valuing redemptions is much more complex than pricing the cost of acquiring points, but that shouldn’t be an impediment to getting started with earning!

Suffice to say, there are incredible gains to be had, even if you are restricted by the amount of spending or fees you can put in.

Either way, it’s worthwhile to bump first-purchase or first-year-free offers up your list. These are no-brainers that have very little impact on your ability to add to your earnings in other ways, assuming you can spare a credit inquiry.

Calculate Your Gains Now!

If you’d like to start using these equations yourself, I’ve set up a simple interactive calculator.

Plug in the numbers for your credit cards and you’ll see the outcomes for each metric. Play around with the values as you start to understand the relationship between each metric and different types of cards and offers.

In the future, I’d like to incorporate this type of information into our credit card valuations too.

|

Welcome Bonus Points |

|

|

Spend |

|

|

Earn Rate points per dollar spent |

|

|

Points Value cents per point |

|

|

Perks e.g., cash value of lounge access, Buddy Pass, etc. |

|

|

Annual Fee |

|

|

Transaction Fee as a percentage, e.g., 2.5 for 2.5% |

|

|

Cash Rebates |

Conclusion

Measuring the value of your miles and points is not always easy, and nothing is ever truly free or unlimited. Loyalty programs can appear arcane and frivolous to beginners, and I find it helpful to have standardized metrics to fully understand how the benefits stack up, especially when juggling many rewards currencies.

Of course, there are countless other considerations that may tweak how you define “value” – this discussion only scratches the surface. There’s no universal “best metric” as we all face different constraints.

I’ve outlined three primary ways that we might use to measure our earnings: Net Gain, Return on Spend, and Return on Fees. All three measurements can be useful on their own or in tandem with each other. It’s up to you to choose how they best capture your situation as you track your progress towards your goals.

I hope I’ve sparked a curiosity about new ways to view your points, if you haven’t considered these ideas already. Feel free to chime in with your perspectives on how you calculate your points earnings in the comments below, in the Prince of Travel Elites Facebook group, or in the Prince of Travel Club Lounge on Discord.

Thanks for the analysis. Works great for apples vs. apples but not all points/programs are created equal. The currencies and programs are so different- trying to compare BMO points vs TD points vs Scotia points vs Avion points etc. You have to factor transfer partners, cash-out rates, redemption restrictions, multipliers/bonus categories etc. etc.

Totally agree. The best we can do to equalize them is incorporate all of those factors into our subjective valuation of each points currency.

And we already do that a bit here. I recall Ricky used to value MR higher than its transfer partners due to the flexibility of keeping them as MR until you had a redemption ready. However, as people began transferring points immediately, he reduced the valuation to that of the highest-value transfer partner, as that flexibility no longer had any value itself if it wasn’t being used.

Hi Josh, can you please help me work out the #s on CIBC Aeroplan Infinite Privilege vs Aventura Infinite Privilege? Trying to see which is better.

In the future I’d like to make more tools for card comparisons!

For now, for Aeroplan, only plug in the portion of the welcome bonus that you plan to achieve. For example, it’s 75,000 points with $24,000 minimum spend, 45,000 points with $3,000 minimum spend, or 20,000 points with no minimum spend.

For Aventura, I’d value points at 1cpp, or higher if you’re targeting a specific redemption on the Aventura Airline Rewards Chart. Don’t forget the travel credit rebate.

Thx Josh! So many cards, hard to decide. Great article!

Great post! Points and earning measurements are my single most important consideration before using up a valuable hard pull. I have primarily used return on spend but appreciate a new method of return on fees that you discussed.

Have you noticed that opportunity cost increases in the case of cashback cards? Some cards pay annual cashback and you have to put some spend on that statement to access that benefit. If I am getting $200 cashback for spending $2000. My rate of return is essentially 200/2200*100=9.1% and not 10% as advertised

Thank you! Glad to hear I’ve piqued your interest with a new way to look at it.

Some banks do let you apply cashback rewards to a zero or credit balance, and issue you a cheque/etransfer/deposit for a credit balance when you close the card. But this just highlights my point that Return on Spend isn’t as clear-cut or useful as it may seem.

You should really be looking at *marginal* returns (on spend or fees). That is, *compared to my next best option* what does this card get me?

For example, if you have a 2% card with a $100 annual fee and a 1% card with no annual fee, that 2% card is only worth an extra 1%. Hence you’d need to spend $10k to break even on it, not $5k.

Absolutely. Stay tuned for a future post on marginal returns and break-even points!

Ya break even point a good one. Especially for cashback cards. For example Cobalt vs Scotia momentum IV. Which one you got?

This concept deserves a video. A calculated way to describe “value” rather than a general rank.

I agree – it’s a bit tricky, so it helps to communicate it in different ways. I’ll see if Ricky can wrap his head around it 🤪