Today I wanted to take a deep dive into the dark underbelly of this game we play: the cottage industry of buying, selling, and brokering points.

In this shadow world, the familiar concept of “value” takes on a very different significance, the threat of the airlines’ revenue management teams looms constantly large, and the few brokers who manage to perfect their craft can make spectacular fortunes for themselves.

Before we begin, let me warn you that buying and selling miles is fully legal but is against the terms and conditions of virtually every major loyalty program out there, and is potentially subject to penalties such as account closure and the cancellation of any award tickets issued. So if you’re someone who always does things by the book, then this article may not sit right with you.

As we know all too well, though, writing and enforcing the terms and conditions are two very separate things, and the mere existence of these terms and conditions doesn’t stop the underground mileage industry from transacting millions of frequent flyer miles per day, if not more.

While I’m obviously not going to openly encourage you to defy the terms and conditions and participate in the unofficial mileage trade, that doesn’t mean we can’t have an open and honest discussion about it here, which I think many of you would find quite interesting.

I’ll begin by giving you a rundown of how the industry works in general, and then discuss the implications to your earning and redeeming strategies should you choose to take part.

How the Industry Works

Think about the “value” that you capture in earning points through credit cards and then redeeming them for expensive flights and hotels. It’s one of the core tenets of the game that you learn when you’re first starting out: Miles & Points essentially boils down to a form of arbitrage, where you earn points as cheaply as possible and redeem them as “expensively” as possible, thus capturing the value that lies in between.

At whose expense is that value coming from? The airlines and credit card companies, of course. They’re the ones who have set up this whole ecosystem for us to play in, hoping that you’ll be more loyal to them as a result, and also that you may falter somewhere along the process and end up inadvertently giving them a large chunk of your money through annual fees and interest payments. Of course, a large number of people out there are doing exactly that, which gives space for the savvier players among us to thrive.

The entire shadow industry of mileage brokering is based on spreading that value around. A rundown of the various actors in the industry will help explain.

Sellers

Sellers have earned tons of points – whether it’s through running a business, high volumes of credit card spending, or frequent travel on paid tickets – but they might not be able to redeem all their points at high value.

Maybe they’re too busy or inflexible to take advantage of award chart sweet spots, or perhaps they simply don’t care about Miles & Points and would rather have some cash for themselves instead. For whatever reason, they’re looking to part ways with their miles at a favourable price point.

Buyers

Buyers want to travel on expensive plane tickets (typically business class or First Class), but don’t necessarily have the miles to do so.

For example, think about people who live anywhere else in the world besides the US and Canada, where signup bonuses are much more limited – how do our international friends play the game, in the absence of the easy points-earning avenues that we have? Simple: they buy points at a favourable price point and redeem for business class.

Sometimes, the buyers can also be travel agencies who use the miles to redeem business class tickets at a discount for their clients.

Brokers

Now, the sellers and buyers would appear to be able to easily meet each other’s needs here – except there’s an insurmountable “friction” in the market: the practice of buying and selling miles is banned by airlines and loyalty programs, so neither sellers nor buyers feel comfortable openly advertising what they’re seeking.

And that’s where brokers come in to play. Brokers have built up their reputation and trustworthiness over many years of word-of-mouth referrals, meaning that both sellers and buyers are willing to work with them, and are further willing to pay an additional premium for the trust and security that the broker provides.

This premium is effectively built into the broker’s spread between the selling and buying price, and represents the broker’s profit.

Airlines & Loyalty Programs

Lastly, the airlines are constantly looking to clamp down on people for buying and selling miles – some more actively than others.

Air Canada and Aeroplan, for example, are known to be extremely lax in this regard, whereas the infamously draconian American Airlines will even go so far as to include a tracking pixel in booking confirmation emails to see if those emails get forwarded (if so, American takes that to be a reliable sign of mileage brokering activity and will follow-up to investigate).

An Illustrated Example

An example should help clarify even further. Let’s imagine that you’re sitting on 150,000 Amex MR points, which you don’t really see yourself using in the short- to medium-term future.

You could cash these out at 1 cent per point (cpp) using the refundable hotel trick for a $1,500 gain, but you also wonder (as I’m sure many of you have wondered in the past) if you could do better than 1cpp.

You scour the web for mileage brokering services, and find one that offers you a rate of 1.4cpp, meaning that you’ll get $2,100 for you 150,000 MR points – that’s $600 better than if you were looking to cash them out yourself.

Now, obviously, the process of selling your miles is fraught with risk. There’s risk for you as the seller: the broker could accept your miles and then vanish with no trace, leaving you with no recourse (it’s not like you can complain to the loyalty program either, since the practice is explicitly forbidden by the terms and conditions).

But depending on the specific mileage currency involved, there’s also risk on the broker’s side: for example, they might use the miles they buy from you to book a ticket for their buyer, but if you still have access to the account afterwards, you could always go ahead and cancel the ticket, complain to the airline that your account got hacked, and scam the broker out of their money.

Clearly, trust must be established before working with a broker on a regular basis, but how do you establish that trust on the first transaction? You can’t, really – unless someone you personally know has also used the broker’s services and can vouch for them, you must simply take a leap of faith.

Let’s imagine that you go ahead with the transaction: you’ll be asked to transfer the Amex MR points to an Aeroplan account that the broker provides. Upon receiving the miles, the broker sends you the payment for $2,100, and everything is done and dusted on your end.

But what happens to this account with 150,000 miles in it? Well, the broken then sells it on to a buyer within his or her vast network of contacts at a rate like 1.425cpp or 1.45cpp. Effectively, the buyer is paying $2,175 for these miles, and the broker earns a cool $75 from facilitating the transaction.

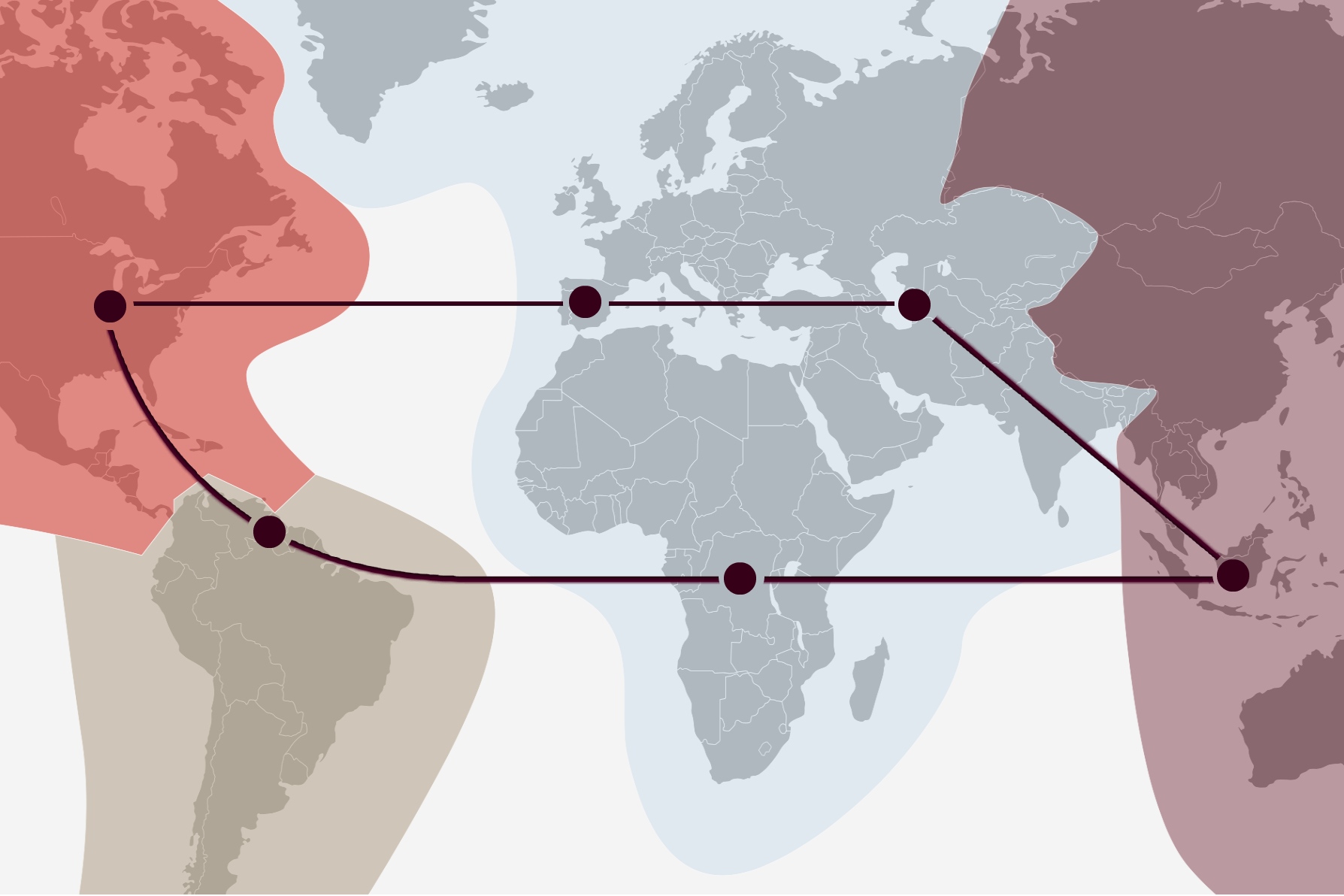

The miles are now sitting with the buyer – let’s imagine they’re a Hong Kong-based travel agency who sells discounted premium tickets to local clients. They might redeem the 150,000 Aeroplan miles for round-trip flight between Hong Kong and Toronto in business class, and sell that flight to a client for let’s say $3,000, thus pocketing $825 in the process.

The Hong Kong-based traveller is also a happy camper, since that business class ticket might’ve otherwise cost him $6,000, so he’s essentially getting an incredible 50% discount.

Let’s take a quick moment to think about the winners and losers in this scenario. You, as the seller, have won – you’ve earned $600 more out of your miles than you otherwise would’ve gotten, since you weren’t going to redeem the miles for anything valuable either. The broker wins, since he or she pockets $75 from the transaction through simple arbitrage. The travel agency wins, earning $825 through the arbitrage process as well. And the traveller wins by scoring a 50% discount on his business class flight.

Who loses? That’s right: Amex, Aeroplan, and Air Canada. They’ve been forced to collectively realize a much higher value for your miles by providing the Hong Kong traveller with a business class ticket instead of providing you, the person who originally earned the points, with $1,500 as you’re entitled to. As you can see, the entire industry rests upon the incredible value that’s waiting to be unlocked in airline loyalty currencies, and spreading that value around to those who would benefit from it the most.

Who’d Be a Mileage Broker?

I genuinely think that the mileage brokering industry would make for a fascinating case-study in business school. Think about it: it really takes nothing more than a solid knowledge base about the airline loyalty industry to get started, and yet only a handful of individuals ever rise to the top.

Every mileage broker out there had to start building their sterling reputation from somewhere. As a broker, you need to be very comfortable with risk: you could always get scammed by your buyers and sellers, and you really have no recourse besides absorbing the losses and chalking it up as the cost of doing business.

At the same time, you also need to be able to keep your buyers and sellers happy, because your reputation is all that counts in this industry. Given the flaky nature of the business, a single online review saying that you’re unreliable could be the death of your business.

Finally, you need to be comfortable playing an endless game of cat-and-mouse with the airlines’ revenue management teams, some of which are more eager to prowl than others. For example, as I’ve mentioned, American AAdvantage is notoriously heavy-handed, so many brokers are reluctant to touch American miles at all.

Alaska Airlines’ revenue management team is also pretty strict, and will disable entire mileage accounts (and any tickets that have been redeemed out of that account) if they suspect foul play – as a result, brokers tend to only deal in Alaska miles that have never received any hotel points transfers before, and even then, they typically require login access to the account to safeguard the tickets they book.

On the contrary, Air Canada and Aeroplan seem to care much less compared to their American counterparts. I mean, just look at Aeroplan’s casual attitude towards protecting its users’ accounts – if they can’t be bothered to properly address hackers and scammers, what can you expect them to do about mileage brokers?

There’s no doubt that it takes a certain mix of attention to detail, risk tolerance, and interpersonal skills to succeed in the mileage brokering industry, but those who do succeed can reap some truly mind-blowing profits.

Some brokers choose to earn their bread on higher margins (for example, they’ll only transact if they can make a 0.05cpp spread, even if they deal in fewer transactions as a result), while others are happy to take on a 0.0125cpp spread if they’re cycling through millions of points per day in volume.

Either way, just think of the vast number of unused loyalty points out there, as well as the sheer amount of air travel that takes place globally every day. It’s really no surprise that massive profits await those who can successfully bridge that divide.

What Does This Mean for You?

As I said, if you’re someone who does everything by the book, then this article should be nothing more than an item of curiosity for you. But if you’re open to dipping your feet into the world of buying and selling points, and thus extracting a little more value out of your unused miles, then there are a few things to take note of.

First of all, the possibility of selling your miles for cash naturally changes the way you think about your miles, since it sets a hard baseline for all your future redemptions.

For example, if you’re open to selling your miles, then you should always be redeeming Amex MR points for at least the market rate of 1.4cpp – redeeming below 1.4cpp would be akin to lighting your money on fire, since you could’ve sold those points for 1.4cpp and used those earnings to pay for your ticket instead.

Similarly, if you don’t have plans to travel in the near future, then the ability to sell miles also means that the bountiful credit card signup bonuses out there can be treated as some meaningful side-hustle income as well. Take the Amex Flowchart, for example, which would earn you 256,500 MR points if you followed through with the four major Amex MR cards.

That’s a cool $3,591 in your pockets; subtract the annual fees of $1,398 and you’re left with $2,193, which can go towards your next home renovation, your kid’s tuition, a new car purchase, or what have you.

As I had touched upon last week, the concept of “value” is subjective to the individual, and part of the way in which this industry specializes in spreading that value around is by opening up more avenues for you to indirectly use Miles & Points to fund more things that matter to you, beyond travel itself.

At the same time, though, there’s an argument to be made that thinking about points purely as interchangeable with cash can take some of the joy out of redeeming Miles & Points for travel.

For example, when you redeem 160,000 Aeroplan miles for an Aeroplan Mini-RTW to Europe and Australia in business class, it’s extremely satisfying to think “oh wow, I only paid 160,000 miles plus $150 in fees for this round-the-world trip.”

On the other hand, it’s decidedly less satisfying to think “I paid 160,000 miles, which I could’ve sold for $2,240, plus $150 in fees, so overall I’ve basically paid $2,390 for this ticket.” Of course, that’s still an incredible discount from the retail price of the business class round-the-world ticket, but it doesn’t quite feel as good as it might’ve felt before you read this article. 😉

So that’s basically the two sides to the coin. There are very good reasons that you might want to sell your points – while it’s expressly against the terms and conditions, thousands of people around the world participate in this industry to their own benefit every single day without getting into any trouble at all.

And yet there are also very good reasons that you might not want to sell your points – maybe your risk tolerance isn’t high enough to stomach the very minimal risk of getting your account banned, or maybe you’d rather just keep the points around for luxurious travel and leave it at that. At the end of the day, it’s all up to you.

Conclusion

I hope this article has given you an illuminating glimpse into the fascinating underworld of buying, brokering, and selling points, which is fraught with risk and opportunity in equal measure. There’s clear value to be gained from all participants in the space, all at the expense of the airlines and loyalty programs, but be warned that choosing to proceed down this path may well change the way you look at your Miles & Points forever!